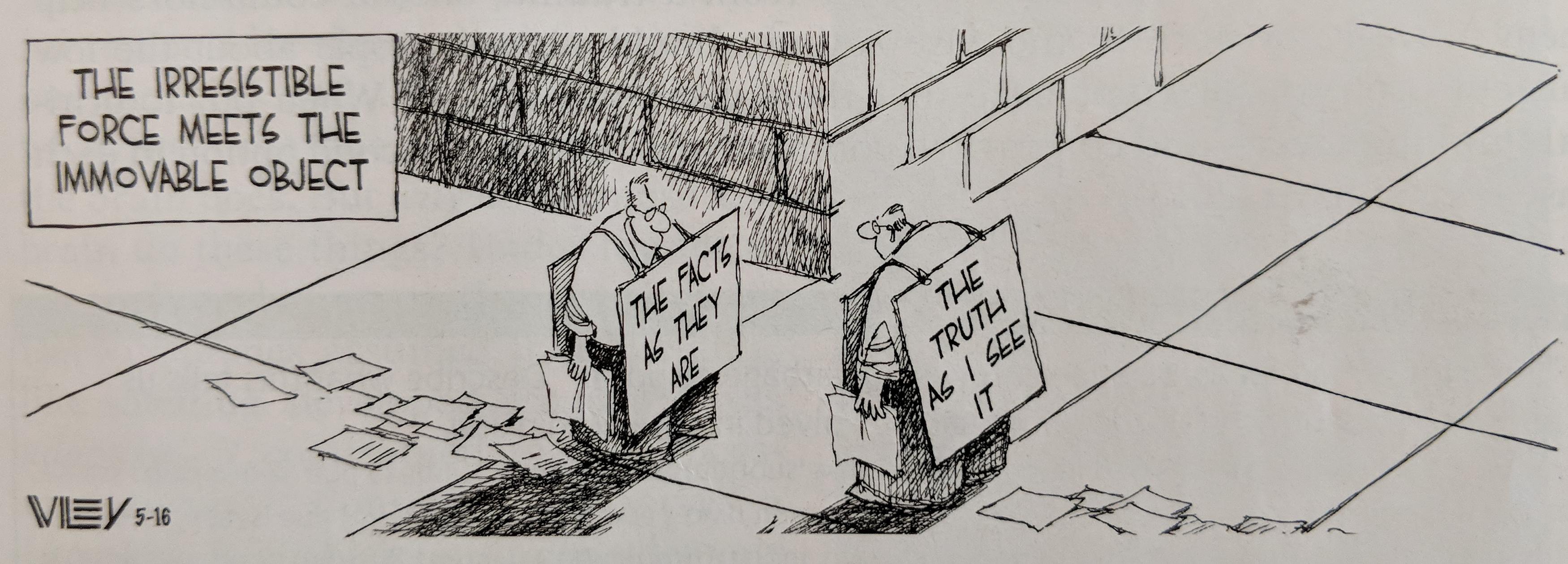

I love a good fact-based discussion, and in keeping with the practice of essay-writing in order to crystalize a viewpoint on a matter, this is my entry into the discussion of opening Portage & Main to pedestrian crossing at grade level. From the early discussion, I noticed a lot of data-based arguments from the “yes” side and a lot of appeals to emotion from the “no” side, so it will take some digging to get to some fact-based arguments from the no side, and some testing of assumptions concerning the data presented by the yes side to verify the sources. The subtitle tips my hand to my conclusion, but the journey is instructive.

When I began considering this a few months ago, I felt like I didn’t really have a dog in this fight; that is, I didn’t have a vested interest in the outcome one way or another. Having spent several years working downtown just a stone’s throw from Portage & Main, I’d been annoyed by not being able to cross above ground, but generally just worked around it using the concourse or jaywalking across Portage East. Then I began to examine the facts and consider what was at stake, and I found myself becoming very clear on the matter.

Somewhere in the midst of the escalating debate on the subject, I discovered that the Portage & Main concourse is actually called the Portage & Main Circus — an observation which bears mention but requires little elucidation.

How did we get Here?

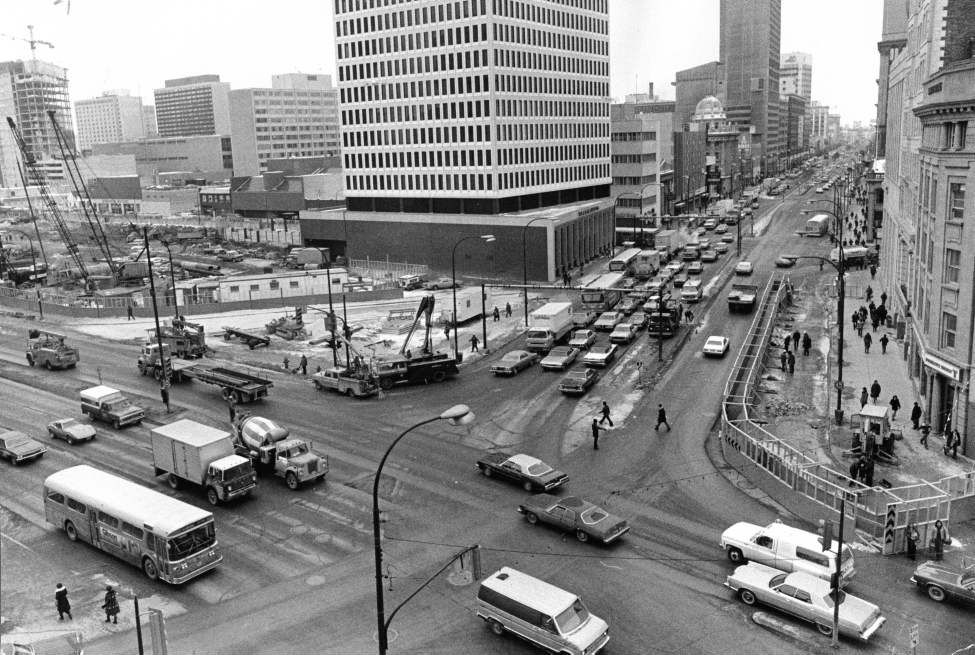

Since 1979 when the construction of the concourse beneath Portage & Main and the connected Shops of Winnipeg Square projects were completed, barriers at the intersection of Portage & Main have been in place to prevent pedestrians from crossing the street above ground. This step was taken contractually as an incentive for developers to construct the shopping mall and office tower so that the Trizec Building1 could be built.

The late 1970s were a trying time for Winnipeg’s downtown. Residents were leaving and businesses were in trouble. Attracting major investment in the downtown area was at critical stage, as the city desperately needed to find a way to breathe life into a stagnating region. Eventually, a deal was struck for a major development at Portage & Main, to include an office tower and underground shopping center, with design provisions for a second tower at some future date. In order to funnel traffic into the shopping area, the city agreed to close the Portage & Main intersection to foot traffic for a period of 40 years, beginning in 1979 with the completion of the project and opening of the new building, shops, and concourse. The concourse itself cost the city $7.3 million, or $22.2 million in 2016 dollars.2

[When the intersection was closed to pedestrian traffic in 1979,] Winnipeg was struggling, Main Street was struggling, the downtown was struggling and there was really a sense that we needed to do something of a mega project. Really, a lot of it was driven by desperation planning. We were desperate for development and to address a declining inner city.3

Jino Distasio

1979 Also saw the opening of the Eaton Place (now Cityplace) mall, as major investments were made to help turn the tide of Winnipeg’s downtown. Portage Place mall followed in 1987, and improvements to the Exchange District have been ongoing from 1976 up to the present. It was declared a National Historic Site in 1997.4 In many respects, these initiatives seem to have worked — the number of residents in the area increased and downtown became a draw once more. It would not be a one-time permanent fix: the tide had been stemmed, but 1979 also saw the opening of the suburban St. Vital Shopping Center followed by Kildonan Place the year after, as the suburbs continued to hold their own.

In the 2014 Civic Election, Brian Bowman5 won a decisive victory over his next-closest rival, taking 47.5% of the vote. Among the main election issues at the time, Bowman campaigned on a promise to remove the barriers to pedestrian crossings at Portage & Main, and this he absorbed as a part of his mandate. In 2017 and 2018, consultations began to be made toward this goal, so that things would be underway in advance of the expiration of the agreement to keep the crossings closed. It was looking like things were moving toward reopening the first of the crossings in 2019 when city counsellors Jeff Browaty and Janice Lukes proposed a plebiscite6 in conjunction with the 2018 civic election by putting the question to the general public. The motion was carried in a near-unanimous vote that included Bowman for the affirmative. At that point, it may have looked like saying “no” was anti-democratic despite Bowman already having won a clear mandate to open the intersection to foot traffic.7

For my part, I disagree with the plebiscite. Not that I’m undemocratic in any sense, it’s just that as noted above, this particular issue had already been decided and shouldn’t need revisiting. Further, as evidenced by the fact that this is the first plebiscite in Winnipeg in the last 35 years, this isn’t how we generally govern, except for major questions where public opinion is warranted. The Winnipeg civic election of 1983 included referendum questions on bilingualism and nuclear disarmament.8 Referenda were employed in decisions leading up to the 1972 amalgamation of Winnipeg with surrounding municipalities.9 Those represent much more significant questions than Portage & Main, which is a matter upon which we expect our elected politicians to act based upon their examination of the facts at hand. Indeed, that’s how it was handled when the intersection was closed in 1979, with no special voter input.

As urban planner Brent Toderian explains, this is not a good type of issue for a referendum vote. Since we’re there anyway, I personally find it incumbent upon voters to become educated on the issue, enough to appreciate the facts of the matter and to know what subject experts think on the issue, and why.

This kind of decision usually doesn’t lend itself to a referendum, because it can be counterintuitive, and because people who oppose it tend to assume the worst — usually it needs visionary leadership to get it done, and afterward those who were against it tend to observe that the “world hasn’t ended” and the results are actually a lot better and more successful than they anticipated.10

Brent Toderian

Recent news has come out that plans from the late 60’s called for the razing of the East Exchange District for new development.11 Clearly, the downtown had been struggling in need of major development for quite some time before the walls went up at Portage & Main, and we almost lost part of what would become a National Historic Site as City Hall struggled to put together a vision for the downtown core. Whether or not we accept that the Trizec deal to close the intersection to pedestrians for 40 years was the right deal for the time is irrelevant to the current question. This is a different time with different needs to address a different situation, no matter what similarities might still be found.

In the end, Portage & Main was closed to pedestrian traffic in 1979 for one reason, and one reason only. Before committing to build, the Trizec Corporation wanted to ensure that traffic would be diverted through their new shopping mall for the next 40 years. For its part, the city needed the development, and was deperate enough to capitulate.

Time’s Up: To Open, or Not To Open?

Now that 40 years has come and gone in the slow blink of a whole generation, we have a decision to make. And thanks to the political wrangling of some opponents of the idea, we’ve got to vote on it, meaning we all need to become informed enough to do so rather than leave it to the elected officials. Do we reopen the intersection to foot traffic, or not?

The Current State of Affairs

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Photo: Ian McCausland

Way back when I was in high school, I had a teacher explain to us how to make decisions. “One option,” he explained, “is ‘Do Nothing.’ Always start your list with ‘Do Nothing’ because it’s always an option, even if it’s rarely the best one.” This has been our approach to the Portage & Main intersection for the past 40 years, and it turns out that 40 years of road salt plus neglect tends to erode even concrete. As documented in a great photo essay by Ian McCausland,12 the barriers and other infrastructure are showing their age, having deteriorated to the point of exposed rebar. Other reports include the presence of mould and asbestos in the underground areas. Looks like we have to start by crossing “Do Nothing” off of our list of options, which now looks like this:

Do Nothing- Fix/Repair/Rebuild only, leaving everything basically the same

- Fix/Repair/Rebuild to allow pedestrian crossing at street level

- Fix/Repair/Rebuild to allow pedestrian crossing at street level *and* reimagine the intersection’s outdoor public spaces at street level

For the purposes of discussion, let’s go ahead and cross off option 4, for the reason that reimagining the outdoor space is not necessarily tied to whether or not the intersection is open to pedestrians. Naturally it doesn’t have quite the same impact to reimagine the spaces on the intersection’s outdoor corners if there’s no additional foot traffic to enjoy it, but it could still be done. Besides, there’s a lot of wiggle room in what happens at the intersection, and we really want to boil down the options to simply open or closed. What we do know for sure is that we have to spend money on it, we need to do repairs and modifications, and that construction is going to mean lane closures and other inconveniences. Let’s put that on our list of “givens” and say the only remaining questions are the cost and the end result.

The Cost of Portage & Main Reconstruction

Thanks to a report commissioned by the City,13 we have an early indication of what the impact will be of opening the intersection to pedestrians: $11.6 million. Unfortunately, due to the late decision to send the question to a plebiscite, we don’t have the comparative estimate of repairs which need to be undertaken whether the intersection is opened or not. The City has issued an RFP to provide such an estimate,14 but the RFP closed in July and it’s too early to expect any results, which may well not be available before election day when this question goes to a vote. The final results are due October 12th per the RFP, but the award was 10 days later than planned.15

So just what does $11.6 million buy you these days? First, $5.5 million of that gets you additional new transit buses.16 This addresses some changes to transit service where additional busses would be needed according to the Dillon report,17 but it’s not clear exactly how or where these would be added. Since each new bus costs approximately $500,000,18 this means we’re talking about 11 new buses. In context, Winnipeg Transit purchases 32 new buses every year as it maintains its fleet of over 600 buses.19 A helpful comparative measure that’s not readily available would be the cost of adding buses and staff to address new or amended routes for new subdivisions of the city like Waverley West, Bridgewater Forest, Sage Creek, and others. It’s hard to know how routine changes like this are as routes and ridership numbers change over time. It might be assumed this change is more than routine, but that hasn’t been established, and if it is more than routine, we don’t know by how much.

$3.5 Million has already been approved by City Council in 2017 to cover some repair and planning for opening the intersection to pedestrians. The latter part will be on hold for the time being, but we don’t know the split between these two items in the $3.5 million. Presumably some of this repair work is necessary just to tide things over, but that’s not explicitly stated.

The $11.6 million (and the $5.5 million) does not include $1.9 million in additional annual operating costs for Winnipeg Transit, which includes 12.5 additional full-time staff. One might spin this as a new job growth opportunity from opening Portage & Main, but again, these numbers would be more meaningful if we had something with which to compare them. As it is, they are just numbers, and we don’t know explicitly if the costs are something which Winnipeg Transit can take in stride. Since they already employ 1,560 people,20 this is less than a 1% increase in staff numbers, so presumably has less impact than a change in the payroll tax rate would, and certainly less than a fluctuation in the cost of diesel fuel.

Why Keep Portage & Main Closed

I’ll start with the no arguments, since we were already on the course of opening up the intersection when this came up. Besides, you have to start somewhere. This won’t be an exhaustive list of arguments for either side, but I will try to represent the best and the most common or vocal arguments for each, and consider them in turn.

Presumption of Purpose

I’m going to start by quoting Councillor Jeff Browaty:21

Earlier this year, Browaty referred to the proponents of opening the intersection as “elites,” implying they are out of touch with the concerns of average residents. He now says that was the wrong word. But he argues that many of the people lobbying for change do not actually use the intersection. And he thinks they are nostalgic for a lost era, before the arrival of malls and big box stores, when the intersection was a hopping retail hub. “Opening Portage and Main isn’t going to bring all of that back,” he said. “We’re not recreating 1950s Winnipeg by opening Portage and Main. I think that’s where some of the Yes people are trying to go.”22

Jeff Browaty

It’s unwise to make assumptions about why an opponent is arguing a certain point, and even more unwise to do it in the media, but there’s a longstanding political tradition for it, and it does tend to score points in that arena. Let’s push past the rhetoric and equip ourselves to deconstruct a couple of different types of baseless statements. Browaty initially responded to statements by a small group of people who voiced early support for opening the intersection and founded VoteOpen by calling them “elites” – in this quote, he backs off from that word, but leaves his criticism on the table.23 Whether they use the intersection or not isn’t actually relevant, since that’s not a prerequisite to hold an opinion or to vote on this plebiscite. In fact, using the intersection is no valid indicator of whether or not one is “in touch” with the issues. The real problem, however, is that this part of the argument is an ad hominem attack — it’s an attack on the proponents themselves rather than upon their argument. This may in fact be the most common of logical fallacies. Whether or not you’re ugly and your mother dresses you funny is no reflection on whether your argument has merit, but if your opponent is pointing it out, it’s an attempt to discredit you without actually engaging what you’re saying.

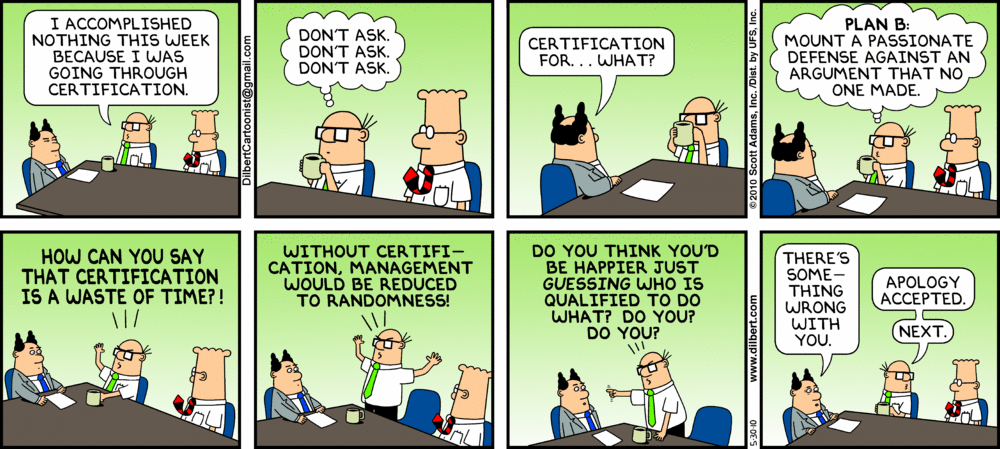

The next part of Browaty’s statement ascribes a motive to the proponents, essentially that they want to bring back some kind of 1950s nostalgia that isn’t coming back. This is what’s known as a strawman argument. By setting up some type of argument that’s a bit outlandish and putting it on the lips of your opponent, you can easily pull it down and thereby make your own argument look like the better alternative. The gist of it is that if you can’t see a flaw in your opponent’s argument, insert one and call it out. The problem with a strawman argument is that nobody is actually using it, and typically, nobody ever would since it will be a fundamentally weak and flawed one. This is definitely the case here, as nobody has voiced what Browaty is claiming, and by pulling down the strawman instead of the actual arguments, he again avoids engaging in a fact-based discussion in any meaningful way. As such, despite presenting one of the earliest arguments or rebuttals for the no side, there’s nothing of substance in these statements that we can enter into the ledger. Browaty has stated he’s been against opening up the intersection since back when Sam Katz was mayor,24 so his opposition is longstanding.

In any event, this exercise primes us for better evaluating arguments for and against opening the intersection. We’re looking for substantive fact-based arguments, and cannot enter anything else into a pro/con ledger since they aren’t actually relevant to the decision.

Another presumption of purpose is presented by mayoral candidate Jenny Motkaluk, who (along with Browaty) used questionable language in the characterization of the intersection opening as Brian Bowman’s “vanity project.” Motkaluk called the current mayor “sneaky” for hiding the source of funds for the approved $3.5 million toward the project.25 Both phrases form a kind of ad hominem attack which may not directly level any charge, but is clearly worded to disparage the person holding an alternate viewpoint. Again, there’s nothing of substance here to put toward the question of opening Portage & Main, for either side.

Various Cynical & Misplaced Objections

A number of additional problematic arguments have been made that can be addressed in brief before moving toward the most substantive of the “no” arguments. There a number of alternate versions of “I don’t want to cross at ground level”, “It’s too cold, nobody wants that”, “Most people want it closed”, and “Things are fine as they are.”

“Weasel words”26 are often used to provide a false type of authoritative weight, such as saying “Most people think…”. Watch for these in ambiguous statements, hyperbole, and euphemisms, including some of this batch of objections, as they represent another form of fallacy. One could simply write some of these off on that basis, but let’s instead probe to see if there are legitimate points in these areas behind the poorly worded arguments.

“Most people want it closed” is an appeal to the bandwagon, another logical fallacy. “Most people” as a group, are not necessarily correct. On the issue at hand, Winnipeg residents are fairly evenly split,27 with 52% favouring the status quo in at least one early poll, so there is technically some merit behind what’s being said, if it weren’t a kind of groupthink fallacy. Democracy does not consist of showing up to vote for what you think is the majority opinion, it’s to vote for what you think is the best option. My personal beef with this thinking is that it’s an abdication of the responsibility to become informed and vote intelligently. As such, it leads to voting for the loudest voice or clearest sound bite regardless of merit, and can result in decisions against the best interests of the majority.28 Both as a logical fallacy and in the interest of thinking for oneself, there’s nothing to log from this argument either in terms of determining which is the better option on the basis of the facts.

“It’s too cold”, “I don’t want to cross”, and “things are fine” are variations of other self-defeating arguments: if these were true, the discussion would not exist. It bears mentioning that the existing underground concourse crossings would remain in place for those who prefer. Despite some misunderstandings, nobody will have to cross the street outdoors, but those who want or need to could be given the option. Indeed, my not wanting to cross the street would hardly be a valid reason to prevent someone else from doing so. And, of course, it’s not always too cold to cross the street outdoors. Despite Winnipeg’s reputation for extreme cold, we’re fine being outdoors for most of the year. As for things being “fine”, we have to openly hear the “yes” arguments before making this statement, otherwise we’re simply writing off the discussion before we’ve gathered enough (or any) information to adequately weigh in on the question. For now, we’ll just acknowledge that things are probably not fine for everybody.

There are Existing Crossings Nearby

The objection that you can already cross just a block up the street is true, but the question remains whether that’s enough. The statement is made to imply that it is, so let’s consider the facts and put them in context.

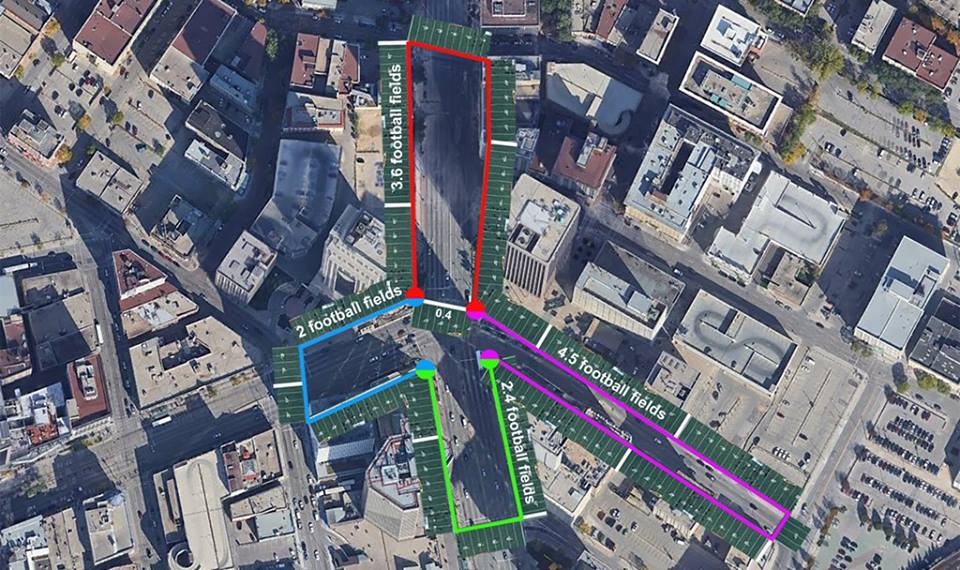

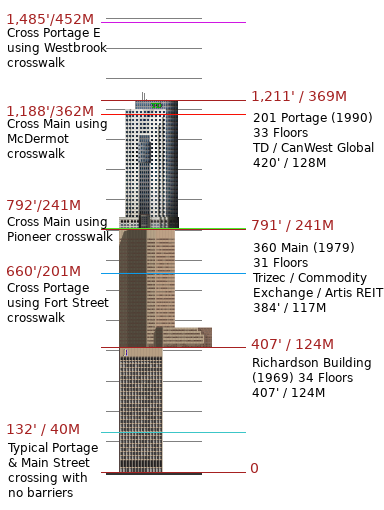

Crossing Portage west of Main (blue path) can be done at Fort (Notre Dame), which about a 220-yard (201 meters) walk.

Crossing Main Street south of Portage (green path) can be done at Pioneer Avenue, which is a 264-yard (241 meters) walk and requires an extra street crossing of Pioneer due to the intersection’s configuration with the crosswalk ending on an “island” boulevard in the middle of Pioneer.

Crossing Main Street north of Portage (red path) can be done at McDermott. This journey is about a 396-yard (362 meters) trip and involves an extra street street crossing of Lombard at Main.

Crossing Portage Avenue East (purple path) can be done at Westbrook Street, which is the farthest travel distance to the next nearest intersection at 495 yards (452 meters), which is more than a full quarter-mile. In fact, if you are standing on the southeast corner of Portage & Main, getting to the northeast corner (across Portage Avenue East) is farther than going “kitty-corner” to the northwest corner by crossing Main Street at Pioneer and then crossing Portage at Fort. In practice, this crossing of Portage on the east side of Main Street can’t always be called the longest of the four crossings, since the normal practice if you’re taking this path above ground is to walk around the barriers and jaywalk across Portage East somewhere in front of the Fairmont hotel.29

The distances here are somewhat extreme, as the distance to cross the street directly would be in the range of 44 yards (40 meters), a reduction of between 80 and 92% in distance to cross above ground. This fact means that the arguments that there are nearby crossings and that it’s too cold to cross outside should probably be considered mutually exclusive.30 “Nearby” is something of a subjective word, but one that in most cases simply does not apply here. If they were near enough, there would be no issue and people wouldn’t bother crossing underground at all. In our current scenario, this simply isn’t the case.

The dismissive versions of the existing-crossings argument are “Walk a block!” or “Walk, like 50 feet, okay?” Having examined the required distances, we know that that the distances expressed can be hyperbolic, and don’t take into account the fact that not everyone can walk that distance. Referring those people to the elevators may be well-meaning, but perhaps only applicable during the business hours of the office buildings where the elevators are located.

So far, we’ve done an overview of some the simple objections and some of the counterpoints addressing them. We don’t have much for the “no” side of the ledger yet, but from here we move on to the most substantive of the “no” arguments – the ones which are strongest, most recurring, or which warrant the most discussion.

Cost Objections

There’s a proper objection to be made here, since opening the intersection is not free. As the “yes” side points out, neither is keeping it closed and only doing repairs to the barriers, but it does seem that based on information available so far, the cost of opening the intersection is greater that the cost of not doing so.31

First, we should address a fallacy upon which this argument is often based, namely that we have more important priorities. Whether the pet project is parking, poverty, potholes, or pool closures (or a myriad of others, including unspecified priorities that don’t start with “p”), the fallacy here is a false dichotomy. There is no binary choice between this and any other priority, and whether or not this project is undertaken is no indicator of whether some other priority will or will not be addressed. Indeed, the City does thousands of projects, initiatives, and ongoing maintenance routines every year, and like this proposed project, each is undertaken (or not) on its own merit. Further, where budget constraints are an issue, there is no interchangeability between the operating budget and the capital budget. As an example, opening Portage & Main (capital budget) has no impact on the budget for the number of police on the streets (operating budget), and vice-versa. Among the various alternate priorities I’ve seen under this category of objection are any number of issues that are provincial or federal government responsibilities rather than civic ones.

An attendant fallacy is the criticism that the estimate is $11.6 million and there will be cost overruns because the police building and other projects had overruns and they always cost more. Whether or not this is true of other projects, there’s no guarantee it will be true of this one – we simply cannot know and cannot test in advance. One of the biases that fuels this notion is what Hans Rosling in his book Factfulness calls the negativity instinct.32 This is the idea that we are conditioned toward thinking negatively by the nature of the news we hear. For example, although airline travel is extremely safe, we only hear about airline disasters – none of the thousands of airplanes that land safely every day make the news for having done so. Similarly, the news media doesn’t report on every project that comes in at or under budget – this simply isn’t considered “news”. “Politician keeps promise” is not a very compelling headline, so it isn’t one you see, just like “Project finishes on budget”. No scandal, no story.33 It also bears mentioning that the estimate figures already include some contingency for cost overruns.

The substantive part of this objection is that the cost is not zero. In perspective, it is quite a small project and is dwarfed by others at present, including the Waverley underpass currently under construction. Where it is deemed necessary or desirable, the City spends a lot on capital projects, as it should in order to keep pace with the needs of a growing city. It should be noted that of the $11.6 million estimate, there is some inclusion for things we don’t yet know are issues but will need to address either way. There is also some contribution to transit costs, as detailed above. In the context of the city’s capital budget, this is not a large project, and although the cost is not zero, it cannot be called exorbitant. As noted above, however, part of the cost is already allocated and approved. Any remaining ambiguity in the cost of a fix-only option is due largely to the lateness of calling the plebiscite.

The cost objection has some unstated or hidden assumptions inherent in it as well, as does the corollary: generally there are assumptions no matter whether you consider the cost high or low, worthwhile or not. In part, this is why I spent some time discussing cost above before delving into its interpretation on either side of the debate. Calculating the cost is neutral information; interpretation of the cost may not be. The question of cost really needs to be rephrased from what it costs to what value is received for the cost. A price tag on its own is just a number. To address the value of opening Portage & Main, we’ll need to wait for the “yes” argument in order to weigh it against the cost.

Traffic Congestion

I strongly suspect this is somewhere near the heart of most of the objections, either directly or tangentially. For example, safety (which we’ll consider next) wouldn’t be such an issue without the traffic. The suggestion that existing crossings should suffice is largely a fear that more pedestrians closer to Portage & Main will slow commute times. In theory, if the same pedestrian is crossing just a few yards up the street, she should have pretty much the same effect on traffic.

I expect that Menno Zacharias is planing to vote no, based on his account of the intersection in the early 1970s when he was a police cadet.34 I enjoyed the history he relates — at the time, police cadets were deployed for additional traffic control in the afternoons, and he remembers Portage and Main being essentially mayhem at the time. He recalls issues from pedestrians crossing after the walk signal had changed, simply to avoid the cold. Opening up the intersection now will not close the concourse, and perhaps much of the late-afternoon commuter foot traffic will remain below ground in these circumstances as they flow from their concourse-connected workplaces in the direction of their target bus stop or parking structure. If it’s too cold to wait for a crossing signal, pedestrians are more likely to stay below ground.

Fortunately, we have some research to address the matter of traffic congestion, in the form of the report commissioned by the City (“Dillon Report”)35 on not only the cost, but also the effect on traffic if Portage & Main were to be reopened to pedestrians. In fact, there is likely no source of data on the whole question that is more relevant than this one document, which is also the source of the $11.6 million estimate. The mandate for the report wasn’t to recommend whether the intersection should be opened, because that was a given at the time – instead, it was to assess the costs, gauge the impact on traffic flow, and make recommendations accordingly.

The report used specialized models to predict the effect on traffic, which turns out to be up to an average of 50 seconds extra during the afternoon rush hour, less during the morning rush hour, and no effect at other times of day. North-south traffic flow on Main Street would face no interruption, so the traffic turning left or right would be most affected. This makes sense given how light cycles work with pedestrians crossing the path of traffic at any normal intersection. Some delays could be longer for certain paths of traffic at certain times, but for the most part, these might seem to be outliers.

In reviewing the traffic flow with projected complication for adding pedestrians, the Dillon Report notes that northbound traffic waiting to turn right onto Portage East would disrupt the northbound flow for through traffic. After considering single or dual right-turn lanes and other options, the report recommends disallowing right turns from northbound Main onto Portage East, which maintains a better flow for northbound through traffic, having eliminated one vehicular path through the intersection. This has been criticized by some, but perhaps without having considered and tested the assumption that change here is bad.

Most vehicular traffic travelling northbound on Main Street and wanting to turn right onto Portage Avenue East is actually better served by turning right at Pioneer and left onto Westbrook, then Portage East, if that was the destination. Using Lombard works equally well. Turning right onto Portage East is the least-used path through the Portage & Main intersection.36

Transit riders in the area would anticipate delays into the 5-minute range, which are at least partially addressed through the associated transit investment recommended by the report. Practically speaking, a 5-minute loss might be regained through the growing rapid transit corridors as they begin to service more areas of the city in coming years. More to the point, some decreased walking distance/time could be realized by transit riders crossing Portage & Main above ground as they move to and from bus stops. After all, it seems a valid assumption that there would be a significant overlap between pedestrians and transit users.

Opponents of opening the intersection are typically focused on the traffic changes, and to my mind, this seems the most valid concern. Thankfully, the Dillon study quantifies this fairly well for our needs at present. Among some detractors, there can be found a sense that the Dillon Report is simply wrong or overly optimistic on this point, and that things will be worse. This actually weakens the argument, since it removes it from being fact-based and data-driven to simply being speculative. Simply disbelieving the expert report would require factual rather than cynical support.

Detractors concerned about traffic flow should refer to the report directly to see the methodology and detailed scenarios that were used to arrive at the averages it did. Upon digesting this information, it must be agreed that this is the most accurate picture we can expect to have at this point in time. It also helps the reader begin to set aside assumptions about how the revised intersection might function, given the available options for light signals (flashing green light, turning lights) and paths like single or dual turning lanes. The Dillon Report includes several scenarios, one of which even has a third left-turn lane from Portage onto Main Street northbound. Clearly if we proceed with opening up the intersection, all these would need to be taken into account (and would be, of course) to optimize the flow of traffic as well as pedestrians.

Safety Concerns

Safety is another valid concern to be addressed, as it should always be when putting vehicles and pedestrians into a shared space. It’s easy to dismiss the hyperbolic objections, such as “There will be blood running in the streets!” as simply being the outlandish statements that they are. For example,

Courier Bernie Pollard… drives through the intersection daily and has safety concerns about mixing vehicle with pedestrian traffic. “That would be a stupid idea, there would be more fatalities within a week than there have ever been since it’s been closed,” [he said.]37

Bernie Pollard

These fail in their polemic attempt. As appeals to fear, they are a fallacious form of argument which are dismissed as such without need for rebuttal. Again, we can go back to the data that we do have based on the City’s 2016 (most recent) traffic report.38 We learn that Portage & Main is not our busiest intersection, and that our busiest intersections do still allow pedestrian traffic. We also learn things like accident rates, and where accidents do take place. Referring to this same report, Alyson Shane sums up well:

According to the 2016 Annual Collision Report from the City of Winnipeg, fatal collisions only made up 0.10% of all motor vehicle collisions that year. This means that of the 17,586 collisions that occurred that year, 18 were fatal. Of those 18 fatal collisions, only 6 (0.034%) occurred at intersections, and only 4 (0.022%) were with pedestrians.39

Alyson Shane

We are taught that the intersection is the safest place to cross the street, and it turns out to be true. Essentially, pedestrians are safer when they are where motorists expect them to be. Not that there won’t ever be an accident, but speeds are lower at intersections where vehicles are turning (and intersecting with pedestrian crossings) and motorists are expecting pedestrians to be there. This would explain why fatal collisions in the cited statistics are less common at intersections. As noted above, the current situation tends to encourage crossing between intersections on Portage East especially, which is statistically far less safe than a pedestrian-friendly Portage & Main would be.

Those who say that safety is their only concern should also consider alternatives for making the intersection safe beside simply resisting change. They might want to advocate for a scramble corner, which includes a light cycle where all vehicles stop and pedestrians can cross in any direction, including diagonally. Vehicles and pedestrians never share the space at the same time.40

In the end, there is no reason to expect that pedestrian crossings at Portage & Main would be any less safe for pedestrians than at any other intersection in the city, including our busiest ones. That said, it should be noted that pedestrian safety is a part of the analysis and planning for the intersection opening, as in the Dillon report. There is, however another consideration with respect to safety, so we’ll return to this subject shortly.

In fact, designing for pedestrians makes intersections safer for all users. One of the key design considerations for streets and intersections is to design for the most vulnerable user, and the rest of the users will typically read the pattern and behave accordingly. All eyes will be on Winnipeg at this decision point, looking to see whether the great leaders in Prairie urbanism zigs or zags when faced with this opportunity at Portage and Main. Winnipeg is a great city, a really great city. Portage and Main the way it is now — closed to pedestrians — is not suitably designed for this city at this time.41

Ryan Walker

A Look at Winnipeg’s Downtown

I’ve saved one cynical objection for last, because the factual part of the response to it transitions into some of the strongest positive reasons for opening Portage & Main to pedestrians. The objection is again an unfounded hyperbolic one that doesn’t really need any refutation, but it jabs at an important subject for the “yes” side, and gives some insight into an attitude that can drive a number of other objections because of the misconception it promotes. Essentially, this is a kind of “leave-it-to-the-wolves” attitude toward the downtown area that perpetuates a false picture of the core as a hopeless slum region that isn’t worth an investment of any kind. There are people in the city who can tell you how many years it’s been since they’ve been downtown, and see that as a point of pride. The trouble is that it’s a fear-based stance that’s not in tune with the reality of downtown Winnipeg.

Nobody Lives There – or Wants to

This defeatist attitude toward the inner city area has established a self-fulfilling stance toward policy in many American cities which put some of their regions into sharp decline. The reasoning that nothing can be done to fix it leads to policy where nothing is attempted. With the inevitably resultant further decline in conditions, the original erroneous assessment is “proven” to be correct, and becomes further self-perpetuating.

The fact is that Winnipeg’s downtown region has been steadily improving, and it’s been growing at a faster rate than the rest of the city.

Over the last 10 years [to Feb 2016], approximately 2,000 residential units have been constructed downtown, increasing the area’s population to 16,000, its highest in the city’s history. …In 2014 alone, 450 new residential units were built. Nearly 400 more were added in 2015, and under construction right now are at least 11 individual projects representing more than 800 new residential units scheduled to take occupancy in 2016.42

Brent Bellamy

True North Square will add 194 residential suites in 2019. SkyCity will add another 380 in 2019, and True North has announced an additional 275 units for 2019-20 for a total of 849 from these 2 projects alone.43

Circling back to the population growth, between the censuses of 2006 and 2011, Winnipeg grew at an average annual rate of 1.5% per year. The downtown grew by an average annual rate of 2.8% — nearly double the city rate.”44 Despite a decline during the 1990s, the downtown population increased from 11,060 in 1986 to 16,800 in 2016 (52% in 30 years). 1986-91 saw 20% growth, and from 2006-16, growth was 25%. By comparison, the city as a whole grew just 3.5% and 14%, respectively.

Lesson: the downtown is sustaining residential growth well above the rest of the city, and doing so consistently for more than the past decade. But who lives there?

For the city as a whole, 51.6% of the population had obtained a postsecondary education, 3.6% lower than the downtown, a significant difference. While 28.6% of the population has a high school diploma or

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

equivalent, slightly higher than the downtown; and 19.8% of the population citywide have no certificate, diploma, or degree, exactly the same as the downtown. Of the 51.6% of the population that have a postsecondary education across the city, 16.1% have an apprenticeship or trades certificate, 31% obtained college or non-university education, and 44.1% have a university education. Of those with a university education, 65.9% have a Bachelor degree, and 34.1% have a University education higher than a Bachelor level education.45

The biggest difference between downtown and the rest of the city is median family income. There are a number of reasons for this, some of which the report mentions, such as family size. While not directly connected in the report, the age of downtown residents is generally lower than in the city as a whole, with fewer 0-19 year-olds but more 20-39-year-olds, including a significant spike in the 25-29 age range.46 In many ways, this would reflect a cohort that is just starting or establishing themselves in a career, being largely single-income households.

A Growing Downtown

The downtown area is effectively growing under different strategies today than what was applied in the past. The Downtown Profile lists some initiatives and investments for the area:

A focus on improving downtown amenities, rather than the “big retail” mall strategies of the 1970s and 80s is helping support and sustain growth. New and redeveloped entertainment/cultural/sporting facilities are helping to bring Winnipeggers back into the downtown, especially during the critical evening period when office workers leave. This has focused on:

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

• The MTS Centre–completed in November 2004 and with changes to the Downtown Zoning, Bylaw kick-starts downtown revitalization

• The Sports, Hospitality and Entertainment District (SHED) – begun in 2010

• Canadian Museum for Human Rights

• Waterfront Drive – begun in 2004. Parks, hotel, restaurants, and some commercial.

• The Metropolitan Entertainment Centre – 2011

• Convention Centre Expansion – 2016

• Parks including the Central Park redevelopment, Old Market Square redevelopment, and the Upper Fort Garry Heritage Park

• Sports related investments such as the Centre for Youth Excellence, the Sports for Life Centre, and the University of Winnipeg United Heath and RecPlex

• Two TIF funded neighbourhood development programs, the Exchange Waterfront Neighbourhood Development Program, and the Sports, Hospitality and Entertainment District Initiative have invested a total of $33 million in downtown street improvements.47

Listing these differently, the Downtown Profile continues:

Investments in the Downtown 2005-2016 (Updated January 2017):

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

• 162 Significant Developments / Investments in the Downtown (Residential, Commercial, and Civic)

• 28 New Projects currently proposed (Residential, Commercial, and Civic)

• Over $3.5 Billion Invested in downtown buildings and key infrastructure (many investments are unreported. We believe this number is higher in actuality).

• Over $1.3 Billion proposed new development (many investments are unreported. We believe this number is higher in actuality).

• More than 2500 new residential units built or under construction (Includes some student Housing, and older adult housing.)

• Over 1000 residential units in the planning/proposed stage

• Population growth in Census Tract 0024 = 52% (the East Exchange and surrounding area, 2006-2011)

• Commercial / Office / Retail Developed: 2.5 million sq.ft. (includes new Winnipeg Police Service Headquarters)

• Educational space developed: 500,000 sq.ft

• Museum space developed: 260,000 sq.ft.

• New Hotels Rooms: 487 built or under construction

• Hotels converted to rental apartments: 2 (more than 500 units)

• 6 New Parkades built; 1 Proposed

• 7 surface parking lots developed

• 3 surface parking lots proposed to be developed (Railside, Parcel Four, 225 Carlton –True North).48

The picture here is decidedly not that of a stagnant downtown which people are fleeing for the suburbs. That particular picture is a holdover from a 1960s and 70s perception, and is part of the situation that necessitated closing Portage & Main to attract development. Today’s picture couldn’t be more different, but maintaining the growth to establish a vibrant healthy downtown area still requires further investment.49 In other words, neglect will stall the growth of the downtown area and by inference, put it back on the stagnation path.

A vibrant downtown region is good for any city, especially if it doesn’t become deserted at 5:00 daily, just waiting for the next weekday morning to show any sign of life.

Why Open Portage & Main

Our cynical objection to downtown investment, rather than being any kind of credible argument for the “no” side, turned into support for the “yes” side when the facts were examined. Having considered the leading “no” arguments, we now turn to the “yes” perspective, asking why we should open the intersection to pedestrians — and why now.

Economic Revitalization

As noted in the Winnipeg Downtown Profile, we’ve seen a marked shift in strategies for the downtown to improve its amenities rather than putting resources toward shopping malls as a draw to the area. This improved amenities track has helped draw more residents to the area, which in turn has supported local businesses such as restaurants and in the case of the Exchange District, a wide variety of retail businesses. Absent the foot traffic from residents, local events, festivals, and restaurant patrons, many of these retail businesses may not be viable. As such, the present strategy seems to be paying off, and should continue to do so provided there is continued investment toward this end.

Making Portage & Main open to pedestrians increases the “walkability” of the area, which is effectively an enhancement to area amenities since they are then easier to reach.

Opening Portage & Main is not the only option to spur downtown revitalization of course, nor is it necessarily the most important one. In other words, it’s not a silver bullet. Since it is in need of repair already (with funding committed to do so), this is the most logical time to open the intersection. Delaying the move by just a few years would mean ripping up recently-repaired infrastructure to do so, with the duplication of the attendant lane closures and disruption from a second construction project.

The Winnipeg Free Press published an article recently50 with a discussion of Portage & Main by a national panel of four Canadian city planners, each having global experience, each being outspoken “prolific voices.” Normally you can find an expert statement to back whatever opinion you need to, but in this case with open-ended questions, they were all unanimous: for the good of the city, the intersection needs to be opened up to pedestrians. From a number of different angles, they opined that this was an urgent issue for the city, one that would have long-lasting effects, and one which the rest of Canada is watching closely.

Thinking back to our discussion about the cost and the need to instead ask what value is received for the cost, consider what urban planner Hazel Borys says on the matter:

Do we want to invest in a way with very low return on investment by redoing things the way they are today? Or do we want to have much higher return on investment because we have made downtown more productive and connected?

Hazel Borys

The major benefit to redesigning Portage & Main as an open multi-modal intersection is a shift toward walkability, underscoring the City as forward-thinking and repositioning it to take advantage of future opportunities. Unfortunately, none of this is quantifiable, either for or against. Nor is it guaranteed, however, all indications from current theory and trends in urban design and planning are that decisions like opening Portage & Main may be complex, but they are essential opportunities to reset the course of our urban design.

If it’s designed well, not only would it dramatically transform the key intersection, better connect things in the downtown and empower the success of the blocks and projects around it — it would also send a powerful message to the community, the market, and those considering coming to or investing in Winnipeg, that the city has turned an important corner toward building the kind of places that people actually love, and that make cities successful.

Brent Toderian

Detractors have claimed that the case for economic development from making Portage & Main into a walkable space has not been well-made by the “yes” side, and this is a fair point on their part. As observed, it’s very difficult to quantify despite expert opinion from the field. As such, there are opportunity costs here that we can’t nail down in advance. Sometimes you have to favour the observations of poets over business majors. Maybe Joni Mitchell really did say it best: “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got ’till it’s gone?”

Then again, maybe I’m just speaking the wrong language, and need to contextualize it for Winnipeggers. Opportunity cost looks like this: “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.” — Wayne Gretzky. The economic development argument is simply this: Winnipeg needs to take more shots.

Accessibility

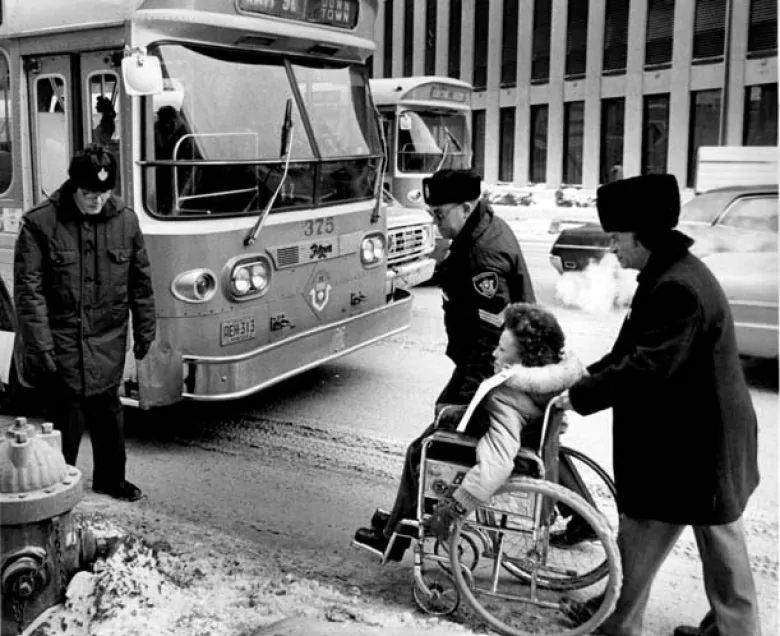

It’s 2018, and we’re thankfully in a different place with respect to mobility issues. By contrast, in 1979 by my recollection, there were still a lot of curbs at street corners that made them wheelchair-inaccessible. At the time when Portage & Main was redesigned and closed, there wasn’t yet much attention being paid to accessibility, and it shows.

In 1979, there was a contingent of people opposed to closing the intersection.51 At the time, some people just hopped over the barriers, for which a fine was eventually imposed. One of the objections even then was about accessibility, but 40 years later, it still hasn’t been resolved in an acceptable fashion.

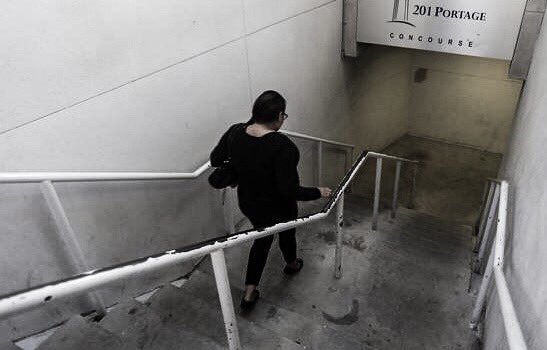

We’ve already addressed the distance to the next-nearest intersection at grade level, which is clearly a big ask for those with mobility issues. They can cross the intersection below grade using ramps and elevators, some of which are inside the nearby office towers, which are not available 24×7. Some trips require the use of up to 5 elevators plus ramps to adjust for the lowest part of the concourse crossing in the circular walkway that actually traverses below the street. In places, there are ramps where a few steps enable the able-bodied to duck below a large pipe, and small-ish semi-open elevators to cover a half-flight of stairs in several places.

For the non-able-bodied, crossing Portage & Main is an ordeal. Add the existing confusion about the path to achieve it that most people experience until they’ve done it a few times, and the burden becomes all the more pronounced.

Safety Concerns, Part II

Safety was a concern for the “no” side, where fear of vehicle/pedestrian collisions turned out not to be supported in any statistical way. Here again we have safety concerns on the “yes” side. Unfortunately we don’t have any statistics here beyond anecdotes, but we need to approach the concern in a slightly different way. This is still largely an emotional appeal, but one where the emotion itself is a part of the concern.

The safety issue that could be alleviated by allowing people to cross at grade level is that the pedestrian doesn’t have to descend a stairwell into a tunnel where they can’t be seen. Outside of business hours, the stairwells and concourse area are hidden from view and often deserted. Compared with crossing above ground in plain sight, the subterranean option puts people at greater risk of assault. Although statistics on the number of assaults in these areas would be helpful, we would have to temper them with the knowledge that a high number of assaults typically go unreported. Of importance to this discussion, there is a related issue of people feeling unsafe in these areas and avoiding the region altogether. If part of the goal is to increase the number of people living, working, and enjoying entertainment in the area, then forcing them into a space that doesn’t feel safe is a direct affront to the goal.

Regardless what the assault statistics for the area might be, the fear of it is real and is enough to keep people away. This is a significant issue, and one that can’t entirely be dismissed by a list of people who don’t feel unsafe. Putting it in perspective requires putting things cautiously, without intention to offend or overgeneralize. The reality is that a significant portion of the population is left vulnerable by walking alone through a deserted out-of-sight stairwell and tunnel.

Of course, I’m suggesting that women are more vulnerable here. I confess this is not something I understood immediately or instinctively about this situation in any way, but through some dialogue and open-mindedness,52 I managed to gain an understanding of something that I cannot know experientially. A very direct example is perhaps the only way to explain it. (Trigger warning for next two paragraphs.)

When a man walks down a dimly-lit alley and sees a dark figure approaching, he might think, “Just keep to yourself, buddy”, or even, “I hope he doesn’t want to make trouble.” There’s a slight rise in the anxiety level he feels, but he just raises his level of alertness and carries on his way.

When a woman walks down a dimly-lit alley (or even a lit one) and sees a dark figure approaching, she might think, “I hope he doesn’t kill me”, or perhaps, “Does he want to rape me and leave me for dead?” Her anxiety level skyrockets well into the fear level and she starts to wonder if she should turn and run, or whether she should have brought her pepper spray.

Of course I’m generalizing, but the fact that the experience can be so different presents an issue with understanding the other side of it. The fact is that as a man, I can have nothing to say against the reality of the fear that many women may feel in this situation — and this is as it should be, because it affirms the validity of the fear. A statistical appeal is irrelevant to it; the only remaining question is how to alleviate it properly, and in the case of Portage & Main, that’s best done by not forcing people into deserted passageways out of anyone’s line of sight.

There’s a counter-argument to be made about security guards and surveillance cameras, but given potential blind spots and response times, it needs to be acknowledged that these are not always going to be effective as preventative measures. In the end, safety is a legitimate concern if the barriers are kept in place. It’s an issue that we ought to exercise caution about if we want to argue against it. The fear cannot be dismissed, and rather than dismissing it as an emotional appeal, we have to acknowledge that the presence of the fear is an integral part of the issue and not just an irrelevant response to it. In essence, whether or not statistics strongly support these passageways as having higher crime rates, the fear of it alone is keeping people away, and it’s the feeling of being safe that will help revive the area as more people can be found enjoying it even after business hours have ended for the day, or the week.

Chicago has an extensive underground network connecting various areas through their downtown. I’ve used portions of it, and would say it suffers from some of the same issues that ours does — there are times of day when I wouldn’t want to use it. But of course, I wouldn’t have to: people can also cross the street above ground at all the requisite intersections, including all along the Miracle Mile, which is quite a wide street. The area is thriving.

Open vs. Closed, the Verdict

After considering the merits of the various arguments, I have to find for “Open.” The arguments on the yes side are for the most part fact-based and data-backed. Perhaps most importantly, they also represent a positive progressive vision for the City of Winnipeg.

In considering the “no” arguments, I found that they were often poorly-stated appeals to emotion or based upon some other fallacy. In order to properly consider any actual arguments, I had to fill in what facts would presumably be behind the sentiments that were actually being expressed. Despite the merit some of them have, none of the “closed” arguments turned out to be compelling. Unfortunately, the rhetoric is compelling, and typically much moreso than that of the yes side. Unfortunately, emotional appeals — particularly in politics, it seems — don’t actually need any grounding in fact in order to be seen as compelling.53

The ban on pedestrians is an unnatural state for an otherwise walkable downtown area with aspirations of multi-mode transportation models, including an ever-growing contingent of cyclists. 40 years is a long time for a concession like this, which was opposed by many when it began. 40 years is definitely long enough for us to start to think it’s normal when it’s not, particularly when forcing pedestrians below ground places an unnecessary burden on many of them. It’s hurting our downtown to not provide the above-ground option.

If The Result is so Clearly Yes, Why are the Polls so Clearly No?

We’re going to try and get to the bottom of this. First, some groups are reporting for their industry or members, beginning with the Manitoba Trucking Association, who wants to keep it closed “on safety and efficiency grounds” until City Hall can hold community consultations and prove that opening it is safe.54 We’ve already considered the traffic safety concern and can set that aside. As well, trucks need to stop at every other traffic-controlled intersection and wait while traffic and pedestrians use it, so there’s really no change.

The real issue here is a traffic plan that forces trucks to use Portage & Main in the first place. If they’re not making a stop in the area, they have no business being there, as traffic through the city should have an available route that avoids the city core. This isn’t a Portage & Main issue, it’s a traffic plan issue — and fixing it could move not just tractor-trailer units away from Portage and Main, but other through traffic as well. This one needs a more forward-thinking approach, and pedestrian compromise is not the way to address it. Forcing the wrong decision on Portage & Main because of this only compounds the wrongs.

Before looking at the latest poll, we can review an older one. Back in 2016, CAA Manitoba released the results of its member poll saying an “overwhelming majority” of its members wanted to keep the intersection closed.55 As it turned out, the “overwhelming majority” of 70% that they claimed was actually 62.5% due to a misinterpretation of data that led to a followup news story to set the record straight.56 The followup piece issues an appropriate warning in its title: “The perils of taking information at face value.” When CBC probed the actual survey results, they found that 65% of respondents drive through Portage and Main one to three times per month or less. Other reported statistics were lumped together in a fashion that overstated the opposition to reopening the intersection.

Collectively these statements from CAA have had the effect of overstating the opposition to pedestrian access to the intersection. The resulting wide dissemination of the initial information through media and social media platforms impacts how Winnipeggers and local policy makers perceive the debate.57

CBC News

In this instance, the results are skewed, but were still widely reported. They are mentioned here as a cautionary tale about interpreting survey results, even as reported by the media. As already noted, the opinion of the majority isn’t necessarily the right one, and should really have less influence than it probably does. What we should take from this is the increased imperative for those who have fully considered the issue to vote so that it isn’t left to the bandwagon.

The majority of CAA’s members don’t seem to be in the demographic that makes much use of the intersection, and I suspect the default sentiment then becomes status quo — the same as for many other Winnipeggers. Once again, this is another reason why this is the wrong type of issue for a plebiscite.

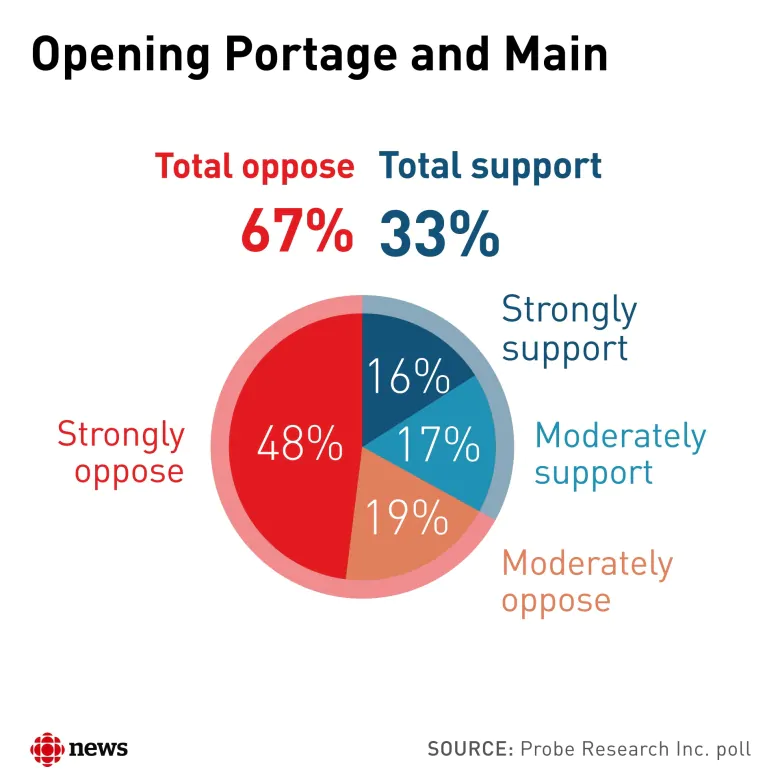

The most recent poll also puts the number of “no” voters at a significant majority, with a 67/33% split against opening the intersection in a Probe Research poll commissioned by CBC at the end of August 2018.58 The poll also says 76% are tired of the debate, perhaps partially fueling negative sentiment toward the question. The poll wasn’t quite done there, as we can glean some further insight from the responses.

The Probe Research poll found the three main reasons Winnipeggers oppose reopening Portage and Main are traffic snarls, the cost of the project, and the potential for collisions between cars and pedestrians.59

CBC News

As we’ve seen at length here, the three main reasons people report for opposing the reopening of the intersection are heavily based on faulty assumptions, misinformation, flawed arguments, or fear. Each of these objections have been met with fact-based, data-driven explanations which reveal the huge overestimations necessary on the part of respondents in order to reach the impact these three reasons have been given. The fourth reason on the list is that respondents felt “it won’t do anything for downtown revitalization, which, as we’ve outlined, can be difficult to conceptualize.60

65% felt that those wanting to reopen Portage & Main were “out of touch with the concerns of ordinary Winnipeggers.”61 This strikes me as an odd question — if almost every Winnipegger is going to see themself as ordinary, they will feel the other side of the question is out of touch with their priorities. In fact, if most Winnipeggers don’t live or work downtown, they may not tend to be concerned about opening Portage & Main unless they can see a clear connection to how it will benefit them. Perhaps this statistic tells us more about the “no” voters than anything else.

The response to this question leads to a characterization of the yes voters by the no voters in a way that indicates a pretty minimalistic judgement of the other side — perhaps a misleading one. There’s only one question on the plebiscite, and given the subject, it’d be a little naive to think it represents the biggest concern of any majority. Even among the most outspoken proponents of opening the intersection, you’d expect to find a number of issues as priorities when they vote for a mayoral candidate in October.62 The thing is, everyone is asked to also weigh in on the question of Portage & Main. It’d be equally fallacious to say that if you oppose opening Portage & Main, it means that keeping it closed is the biggest issue for you.63 Being a proponent of opening the intersection actually doesn’t necessarily mean you think it’s the most pressing issue in the city, just that you have an opinion on this issue (which is good, considering you have to vote on it). It may also mean seeing some value in it that’s not readily apparent to the poll respondent. It’s a terrible question for a poll.

It’s actually very telling to discover that 66% agreed with the statement “smooth traffic through the downtown is more important than pedestrian access”.64 This tidbit, I think, gets to the heart of the objections, viz, that the opponent has little room in their view for modes of transportation other than the car. This should be considered odd, since the entire downtown area is designed for pedestrians and vehicles in shared spaces, with an increasing accommodation for cyclists as well as public transit: Portage & Main is the one exception. The statement implies a false dichotomy: it’s based on the assumption that smooth traffic flow is incompatible with pedestrian access — and as such, I’d reject the premise of the question.

We then discover that 76% of poll respondents say there’s little to no chance they’ll change their minds on the question.65 This is anything but helpful, as it’s not the response of the open-minded. In general, once people understand the arguments for opening the intersection, most tend to come around. Disappointingly, those who won’t hear reasoning from either side will remain entrenched wherever they are, informed or not. As the old adage goes, “Don’t confuse the issue with facts!”

Probe offers some insight on whose minds are made up and aren’t going to change:

• Older adults (50% among those 55+ vs. 37% among those 18-34)

• Those who disapprove of Mayor Brian Bowman’s performance (57% vs. 35% among those who approve).

This could imply that the “no” side is less willing to entertain changing their view, but the statistics given don’t necessarily show that, so it’d be an untested assumption. It does indicate that if you don’t like Mayor Bowman’s performance, you’re more likely to vote against what his primary competitor in the mayoral race calls his “vanity project.”66

I did find a confusing point in the poll data that’s particularly worth mentioning for the sake of anyone reading the summary only. Under “Key Takeaways”, we find this paragraph:

There is virtually no demographic that supports opening the intersection. Young adults (those aged 18-34) are slightly more likely to favour #TeamOpen, but even a majority of those would vote against removing the barricades. Similarly, committed downtowners – those who tend to live, work or play downtown – are more likely to vote for the famed intersection to remain closed.67

Probe Research Poll

Toward the end of the report with the responses to the typical “If the referendum was held tomorrow…” question. There, Probe offers three types of people most likely to vote yes:

• Younger Winnipeggers (36% among those 18-34 vs. 25% among 35+)

• Post-secondary grads (29% vs. 17% among those with high school or less)

• Downtowners – those who live, work or play frequently downtown (45% vs. 17% among those who are not downtowners)68

Notice the apparent discrepancy in Probe’s “Key Takeaway” about downtowners versus their report of the data. The two statements are not actually in conflict, but the summary version without the data cited tends in my view to understate support for opening the intersection. 55% of downtowners may be in the “no” camp, but after accounting for the undecideds (6% overall) plus the 4% margin of error the poll reports, you start to imagine that this segment of voters might actually be in the “too close to call” category.

Since we don’t as yet have a fully finished proposal to look at for Portage & Main, some urban planners are suggesting that voters will lean toward “no” on this issue.69 It’s admittedly hard for people to grasp possibilities which haven’t been fully described, and yet it’s impossible to describe all the possibilities until the design phase is completed.70 It’s a classic Catch-22. There will be many people voting “no” simply because they don’t know what they’d be saying “yes” to.

Are Winnipeggers ready for change? Former mayor Glen Murray thinks we can do it, we just need some courage.71 A lot of discussion is pointing out a variety of projects like The Forks, Bell MTS Center, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and Esplanade Riel, all beneficial projects which likely wouldn’t have gone ahead if people had been asked first. Frankly, it’s easy to criticize in conditions like this. Murray isn’t calling people cowards — he’s just saying that sometimes it takes a little faith, a little risk, to vote yes to something you can’t fully see.

I’m reminded of the real estate television shows where people are walking through the homes pointing at things and envisioning their furniture in the space, saying things like how their couch doesn’t fit well over there, or perhaps that the duvet would clash with the wallpaper. This always stuns me, how someone would accept or reject spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on a home they might otherwise love simply because there’s an issue with their eight-hundred-dollar couch. Really? You love the home, but can’t see any possible solution to making the room match your duvet, or vice-versa? Some people honestly just aren’t good at visualizing things.

“I don’t really like to spend time downtown.” — agree, or moderately agree: 60% of Winnipeggers.72 It’s ironic, the number of people who will vote no to any attempt to improve an area they don’t like.

In the end, the reason for the high number of “no” votes in these early opinion polls might be due to lack of information or imagination — or it might be due to the cultural priority of the personal automobile over all other modes of transport.73 It’s ironic though, for people to want to crush the walkability of downtown from their position in the city’s newest suburbs, which feature roundabouts through disorientingly curving streets with walking paths along the shores of man-made lakes. When it comes down to it, we all want vehicles to drive slowly past our doors and have quick access to nice places to walk outdoors. Unless, of course, we’re just driving through the neighbourhood, in which case all of that is just so much unnecessary annoyance. In all cases, it’s better to maintain a generous attitiude toward the people who live and work in the area.

It strikes me as a kind of NIMBY-esque attitude to force people downtown to not be able to cross the street when there’s no hindrance to doing so in the suburbs (or anywhere else in the city). If you take concept drawings of Portage & Main with wide sidewalks and trees, benches and people milling about with cars in the background, and compare them with concept drawings of places like the Bridgewater Forest’s Town Square, they look disarmingly similar. And they both look very inviting. Now imagine not only protesting someone else’s access to an inviting street scene with a bench and a tree while demanding that people walk an extra 5 minutes down and up flights of stairs and through unwelcoming passageways so that you won’t risk having to spend a little less than an extra minute sitting in your climate-controlled vehicle at a Portage & Main stop light. Because, you know, your bench and your tree are waiting for you if you can just get home fast enough.

An Appeal

I’m frustrated by arguments presented in the media on issues like this. “Walk, like 50 feet!” may be a good sound bite, but it’s a horrible argument, and certainly not the best that the “no” side has come up with. The hyperbole may not be as apparent as you’d expect to someone unfamiliar with the intersection. If a significant portion of “no” voters only drives through Portage & Main 3 times per month, how often do they try to navigate it on foot? Most Winnipeggers will actually go years without doing so.

Emotive quotes and sensational headlines may be good for getting eyeballs onto a news story, but it’s a hindrance to people becoming informed with facts about an issue. The discussion suffers if we don’t hear good arguments from both sides. Someone in a default status-quo position reading a headline about how unpopular something is in a poll is fairly likely to be encouraged toward an “I knew it” response that further entrenches an opinion before facts are even considered. It’s tragically unfortunate that group decisions — especially political ones — are made this way.

I’d love to see media stories able to downplay or point out fallacious arguments for what they are. One side or the other (or both) wants to tell the electorate what to think, but it’d be far better if the electorate could start evaluating the validity of what’s being argued. Or perhaps that’s just too utopian an idea.

The Winnipeg Psyche

This is Winnipeg. Winnipeg in the post-Panama Canal years. We never did grow up to be Chicago. Instead of enjoying the past hundred years as a central hub of North America, we’ve descended into a kind of cynical “not-gonna-happen-here” sort of “good-enough-for-Winnipeg” attitude. It’s pervasive, and we’re all affected by it. In a way, it’s a deep-rooted part of Winnipeg’s psyche. When they tell us something’s going to be good for us, or how it will help raise our profile, we’re skeptical. Truly good things, growth things, prosperity things — those are for places like Vancouver and Toronto, maybe Calgary or Montreal. Winnipeg doesn’t get that kind of glory anymore. Consider your immediate reaction when you see “Winnipeg” and “world-class” in the same sentence, and you may start to see how deep the sentiment runs. This curtails our vision and stunts our growth by causing us to hedge our bets and refuse to take risks. Our natural response is to protest, object, and cling to the status quo. Nobody’s going to make a fool of us again by getting our hopes up. We’re not Chicago. We’re just a flyover city, and we know it.

I confess I’ve been working to shake this way of thinking, and I’m not the only one.74 I can see positive future potential for the city, particularly if we can embrace these kinds of changes — just stop saying no to things. Maybe other people can see advantages we don’t, and if that might be the case, we shouldn’t hold them back. Sure, when I hear a colleague tell me they agreed to a project at less than their normal rate or far below their value, I’m still likely to say, “Dude, you got Winnipegged!” That’s the result of doing business in a city that knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. Yes, it’s a negative view of the city, but it’s one that needs to change. As someone said, “this is why we can’t have nice things.” This is why we need to look past the price and see the value.

We may be a flyover city, but the best way to stop being a flyover city is to stop acting like one. It’s time to end the subterranean crosswalk blues.

Footnotes

- SW Portage & Main, now owned by Artis REIT

- Winnipeg’s Portage and Main closes to pedestrians in 1979 (CBC Archives)

- Darren Bernhardt, CBC News: ‘A desperate time:’ Why Portage and Main was closed to pedestrians in the first place

- Wikipedia: Exchange District

- Wikipedia: Brian Bowman

- CBC News: Voters to decide if Portage and Main will reopen to pedestrians

- Of Bowman’s mandate, I’ve had one exchange with someone from the “no” side who stated that the 2014 vote was simply a “not-Katz” vote, however (a) Sam Katz did not run in 2014, and (b) the assertion is an untestable hypothesis, a logical fallacy. Essentially, there is no way to demonstrate which policy issues earned Bowman the support he received, and his entire platform becomes his mandate. This is simply how politics works.

- Wikipedia: Winnipeg municipal election, 1983

- see Wikipedia: Amalgamation of Winnipeg. Interestingly in light of the the foregoing picture of a declining downtown area in the late 1970s, “[a] government review in 1986 concluded ‘that the unicity structure, with its many suburban councillors and large tax base, facilitated the building of suburban infrastructure, to the detriment of inner-city investment.'” It would appear that the plight of and investments in the downtown area of the late 70’s and following years were simply a corrective to the suburban focus resulting from the city’s amalgamation.

- Winnipeg Free Press: At the crossroads

- Darren Bernhardt, CBC News: ‘Absolute travesty’: 1960s plan called for demolition of Winnipeg’s East Exchange District

- Gallery above

- aka the “Dillon Report“

- Bid Opportunity 614-2018 Closed July 10, 2018 and was awarded to SMS Engineering of Winnipeg on August 9, 2018 for $72,545. The final results are due by October 12, 2018 per the RFP, however it was awarded 10 days later than planned. The turnabout course-change that sent the issue to a plebiscite (July 19th council vote) was so quick that Bid Opportunity No. 587-2018 (unawarded) for revitalization planning for Portage & Main had just closed June 26, 2018.

- This illustrates another reason I object to this plebiscite: being called as late as it was, it’s not possible to provide the public with enough information to fully consider both options. It’s not like the “no” voices on City Council didn’t know this issue was coming or that the mayor was already working on it; they had already voted to approve reports and repair work on it. Presumably, the second estimate provided under this RFP (and the cost thereof) would have been entirely unnecessary if they hadn’t forced this issue.

- Bartley Kives, CBC News: A Portage and Main primer: What you need to know before you vote

- Dillon Consulting: Portage & Main Transportation Study

- Winnipeg Transit: Transit Facts

- ibid.

- Winnipeg Transit: Transit Facts

- Graeme Hamilton, The Recorder &Times: An ‘identity war’ at the crossroads of Canada: Winnipeg debates reopening Portage and Main to pedestrians

- ibid. Personally, I find it ironic that he’s defending a 1960s/70s idea as continuing to be applicable to the 21st century by saying the other side is just nostalgic and the past isn’t coming back.

- For the record, and contra Browaty’s statement, these individuals, some of whom I know personally, do use the intersection and are not out of touch. One only needs to read what they’ve written or said publicly to verify this.

- CBC News: Councillor wants Portage and Main opening on the ballot This opposition predates the Dillon study, so it would be interesting to know his reasoning since we had less information available at the time. Katz also opposed opening the intersection.

- For the record, refer to the October 25, 2017 council meeting minutes, which explicitly states the funding’s source (i.e., from which budgets) as part of the resolution which was carried.

- Wikipedia: weasel words

- Not the latest poll; a more recent one is discussed below.

- Yes Brexit and Trump Presidency, I’m looking at you. If you doubt that that the bandwagon is an unreliable predictor of accuracy, ask yourself whether 8.5 million Nazis could possibly be wrong. The Flat Earth Society has thousands of members, and there remains an inexplicable number of climate change deniers and skeptics.

- This is somewhat damaging to the safety argument for keeping the barriers up for this particular crossing.

- Although for some Winnipeggers, braving ridiculously cold temperatures is a regional badge of honour.

- At least in the short term, financially speaking; we’ll revisit this in the “yes” arguments.

- See Gapminder, The Negativity Instinct